LET ME START WITH THE CLIFFHANGER OF THIS POST:

Let me review: The group CEO of the Fortune 500 company is very publicly preaching circular economy as key to growth. The divisional CEO loves the product concept and is bugging me for project updates. I have a global star-architect as the mouthpiece. I have one of the world’s preeminent corporate design teams whipping up a killer product design, backed by IP developed from one of the worlds best corporate research groups. And a very wealthy, successful real estate developer – THE MONEY – is a global proponent for sustainability and eagerly wants the product from us. So this should be a sure thing, a slam dunk, a series of purchase orders, glorious global design awards, the cover of design magazines…right? Right?????

Innovation is brutal. Sometimes, it can take tenacity stretching not just years, but decades to achieve meaningful change in an industry.

Recently I shared a post on abandoned LED innovation projects from earlier in my career. Surprisingly, that post went on to hit viral numbers on LinkedIn. So let me share another abandoned project – this one from over a decade ago during my time at another corporate behemoth (which I won’t name directly, but I’m sure you can figure it out). But in the end, I persisted in driving genuine industry change.

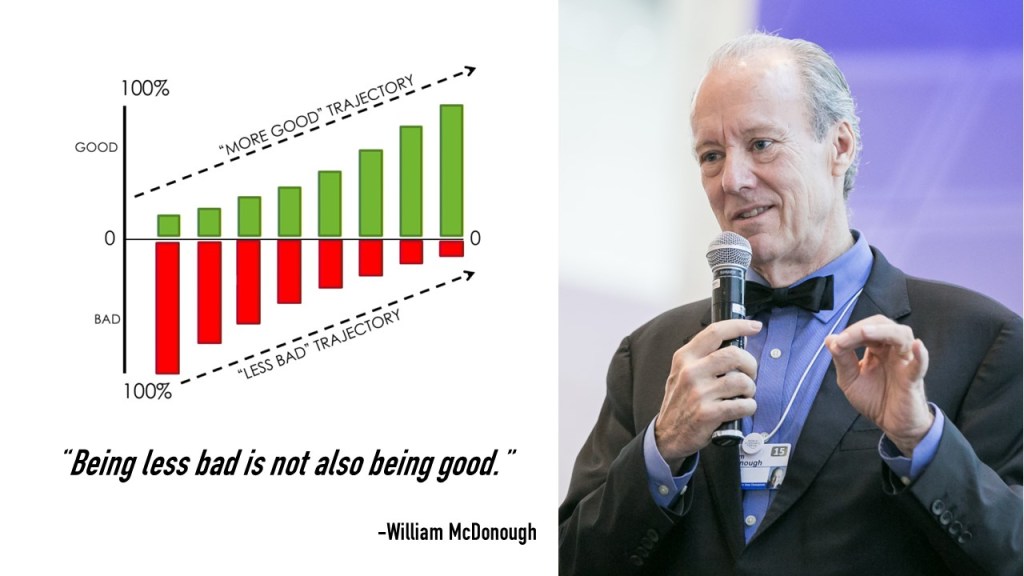

less bad, more good

First, some background: I attended the School of Architecture at the University of Virginia when architect William McDonough was the Dean. McDonough is one of the worlds foremost advocates in sustainable design and manufacturing, most notably having authored the “cradle to cradle” development standard. So when I saw McDonough was speaking here in the Netherlands, I reintroduced myself to him and asked if somehow our innovation group could work with him on a sustainable product design. He immediately responded (paraphrasing) “…well, I’m doing a whole office park development in Hoofdorp, let’s do something there!“

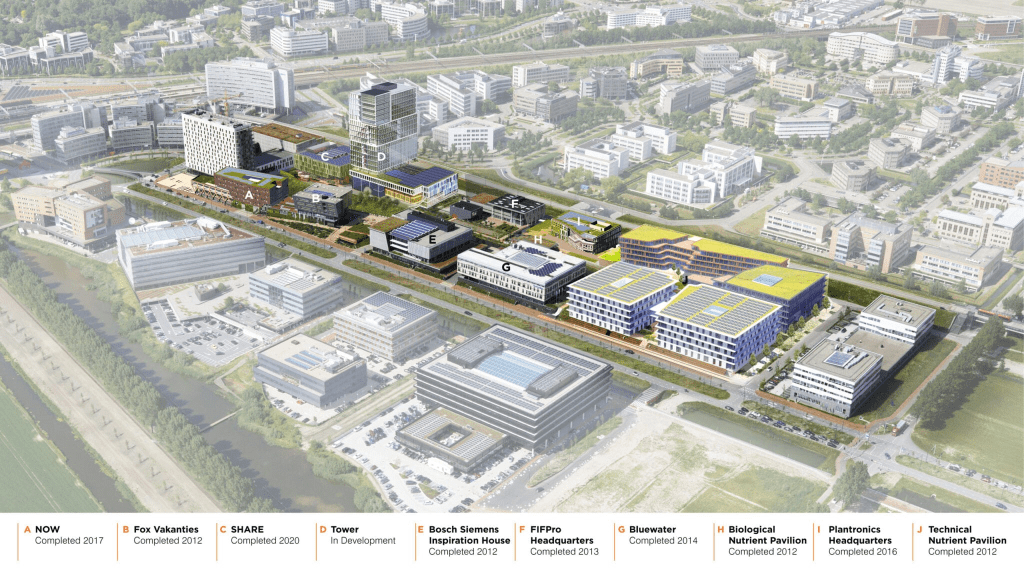

Turns out that William McDonough Partners was designing the masterplan for the ultra-sustainable Park 20|20 office park development not far from Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, along with being the design architect for all the buildings. Park 20|20 is an absolutely gorgeous collection of premium Class-A offices with an intense focus on using cradle-to-cradle design principles throughout. Building Park 20|20 was Delta Development, whose CEO Coert Zachariasse turned out to be a huge global advocate for sustainable design. At the time Delta Development had several buildings completed with many more in various stages of design.

So of course I targeted the highest volume and most iconic lighting piece in an office park, proposing that we could produce a cradle-to-cradle certified linear office pendant. McDonough and Delta were most enthusiastic. Internally within my company, I convinced an ad-hoc team composed of the design group, a prototyping engineering/support group and the research group to contribute to the project, all under the cover and support of my boss at the time, the Chief Design Officer.

stubborn craft knowledge

In trying to lead the project, I encountered this weird mix of eagerness to support the project in concept, but then a stubbornness to embrace any of the actual progressive details. It is a problem I’ve encountered now repeatedly over the past decade in promoting sustainable design, so let me dive deeper:

Throughout the various stages of the project, everyone was well-intentioned, but not necessarily helpful in driving the design forward. What do I mean? Let me take the example of using bio-based materials like wood or bamboo instead of aluminum for an LED light fixture. I quickly came up against engineers and supply chain managers who debated the choice to use engineered bamboo (a fast growth grass with great sustainable qualities) instead of aluminum: If our goal was to design a “cradle-to-cradle” fixture, they were adamant that aluminum was the better choice, because every time it is recycled it doesn’t degrade during processing, whereas wood and other biomaterials degrade each time they are processed.

This didn’t feel right to me. And they wanted to know what “sustainability standard” they had to “design against”, like I was a product manager “tossing a spec over the wall” to them. I didn’t have a good answer for that, either: Ultimately we wanted a high-level gold- or silver-certification from the Cradle-to-Cradle certification program, but that was not a prescriptive standard. It was up to us to choose the materials and methods to achieve the rating.

And by the way, they all know how to design with aluminum, the factories are setup to work with aluminum – not wood, the supply chain has never sourced bamboo, they’ve never certified a wood fixture, etc. The micro-resistance was endless.

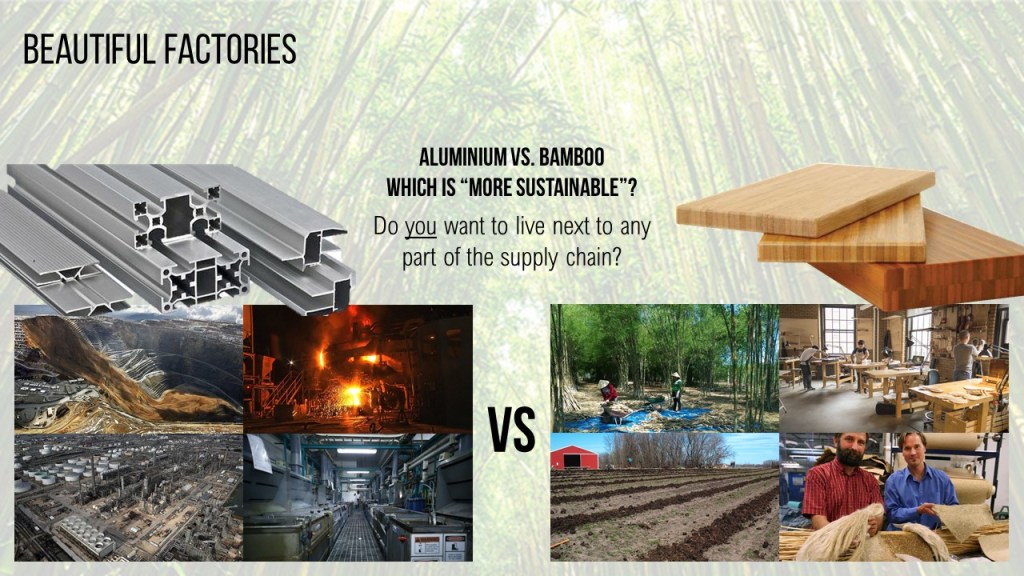

marketing hooks and beautiful factories

So eventually I came up with this response and “marketing specification” for the team: Do you want your family to live next to any part of the supply chain for the materials we are choosing for this product? If you think aluminum is so great, do you want your family living next an open-pit mine? Next to a smelting plant? Downwind of the refinery producing the feedstock for the powdercoat paint? Do you want your children drinking the water downstream of an aluminum anodization plant??? Do you want them to play next to a metal scrapyard?

Of course the answer is a fast NO to every piece of the aluminum supply chain!

But next to a bamboo forest? YES! That increases real estate values. Next a to woodshop? YES! How quaint and local employment! Next to a farmer’s field where the wood decomposes? YES! Yummy organic food!

So the “product spec” became a marketing story-hook requirement: BEAUTIFUL FACTORIES. Every part of the supply chain for this fixture needed to be sustainable and contribute to a better/beautiful social and environmental condition.

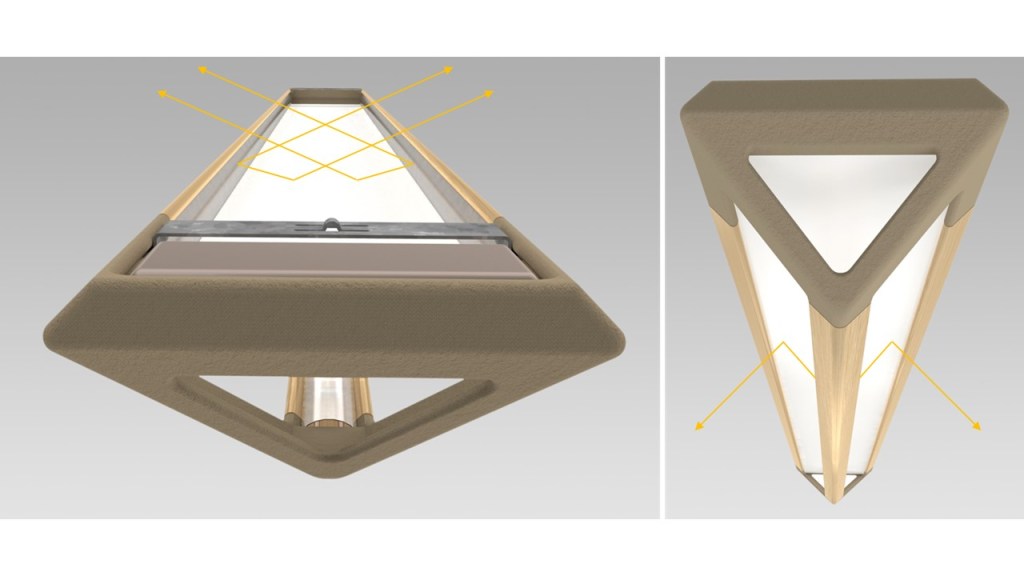

the design

Since this was for traditional open office applications, we developed an iconic shape with a direct/indirect suspended pendant layout, with 2/3rds of the light aiming upwards in a “poor man’s” batwing distribution, the other 1/3rd bouncing off a reflector for a pleasant, bright glow from below. The product team quickly focused on stripping away as many toxic and high-embodied carbon materials as possible. We used engineered bamboo mounting spars as they retained the performance of metal extrusions; a biodegradeable, biomaterial-based plastic for the injection molded endcaps (which would take up much of the complexity without additional components); a very thin high-efficiency white reflector panel (a compromise for efficacy); and a DC-supplied PoE driver to get rid of the high-voltage safety issues.

We focused on design-for-disassembly: Our goal was no screws, no glue – the fixture would easily fall apart into its component pieces at end of life for easy processing. I even imagined a small green tab tucked into the fixture that said “PULL HERE FOR DISASSEMBLY”. What a great little sales “feature” to surprise clients.

A major feat was getting rid of the FR4 printed circuit board for at least the LED strips (the driver still used a traditional circuit board, but we were hoping to get rid of that eventually, too). We used a novel, patented method from the Research group to place LEDs directly onto copper wire strips in a standard pick’n’place/reflow process. The copper wire was enough to dissipate the heat. We mounted this LED/wire strip in a bioplastic clamshell unit to protect the LEDs and structure the strips. I can’t tell you how much resistance we had to this – “experienced” engineers absolutely insisted we needed a heatsink to achieve the needed thermal dissipation. They were so locked in their “craft” that they couldn’t believe it worked even when we built a fully functional prototype. The performance of the fixture was fine, even using 2013-era LEDs, because we fundamentally chose in the design concept to spread the LED wattage over three legs in wide-open air flow.

The design team whipped up some gorgeous marketing pieces to show how the sustainable details could be promoted:

where innovation goes to die

So, let me review: The group CEO of the Fortune 500 company is very publicly preaching circular economy as key to growth. The divisional CEO loves the product concept and is bugging me for project updates. I have a global star-architect as the mouthpiece. I have one of the world’s preeminent corporate design teams whipping up a killer product design, backed by IP developed from one of the worlds best corporate research groups. And a very wealthy, successful real estate developer – THE MONEY – is a global proponent for sustainability and eagerly wants the product from us.

So this should be a sure thing, a slam dunk, a series of purchase orders, glorious global design awards, the cover of design magazines…right? Right?????

It is hard to understand the depths of resistance that daring innovators will find in the bowels of large corporations.

The project died for two reasons:

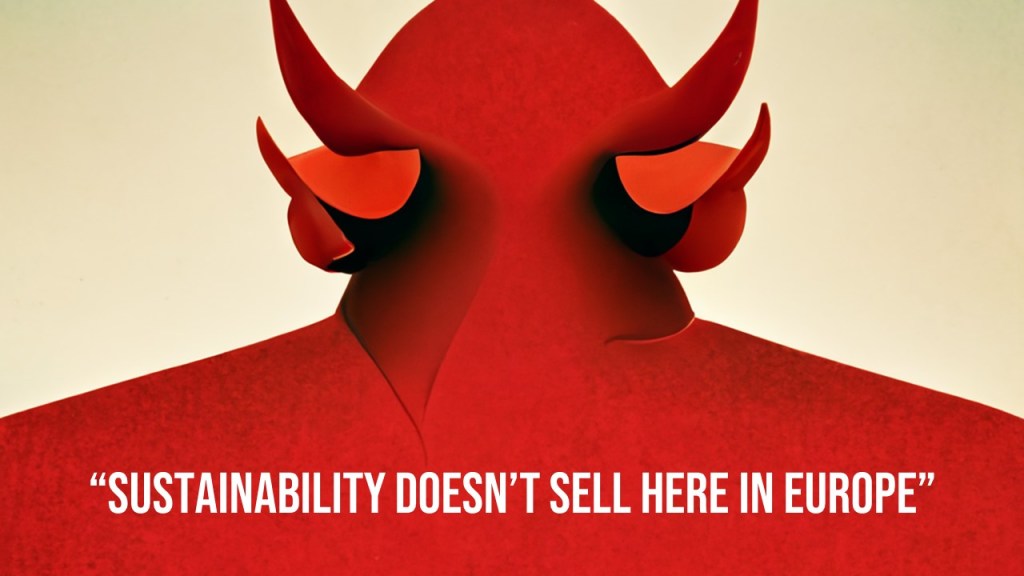

- The company was a heavily matrixed organization. The head of the EU-level product segment group completely refused to support the project. After presenting him the pitch – basically handing him a completely de-risked innovation program with a PO waiting – he told me bluntly that “…sustainability doesn’t sell here in Europe. We already have our program commitments for the year and don’t have the resources to devote to this…” I remember his exact wording like it was yesterday. “…sustainability doesn’t sell here in Europe…” Every team underneath his command put up endless resistance, ranging from exorbitant cost assignments for anything supporting the project, to endless meetings where nothing was followed up on, to refusing to allow the factory teams to help – even though they wanted the innovative product assigned to their teams.

- Another challenge of matrix organizations, this time the cross alignment: The regional sales/market team for where the project was located insisted that a sales manager was already “assigned” to the Park 20|20 development. They “owned” the client and demanded I had to work through them. In reality the guy was basically just an order-taker waiting until the construction team placed an order with distribution. He couldn’t have cared less about promoting some “crazy design project” and dealing with – you know – the actual project developer. He only wanted to make his quarterly number with the least amount of work and risk. A pure commodity-shifting mindset.

Even the most passionate people can only beat their heads against a brick wall for so long. With no way to produce the product and no local sales or service support for the project, there was little I could do. After pushing the project for two years, I eventually gave up and focused instead on a different innovation project altogether. One fully functional prototype of the pendant remained in the sales office of Park 20|20 for years afterward. Orphaned. The client team wondering when or if they could ever get the product.

innovation management, or lack thereof

There is this nasty asymmetry in large corporations: The tireless, long-term efforts of entire functional groups to innovate can be completely derailed by the short-term thinking of a single incompetent manager. Even, as in this case, you have the eager support of the highest level of the company.

I’m a driven person, not a competitive person. I drive innovation projects and creative product developments forward because I want to – I’m passionate to see the change it will bring to the world. For someone like me attempting to drive innovation projects in a bloated, bureaucratic, matrixed organization, it felt like a bizarre game with 100 switches in a row, all wired in series: To make an innovation project come to fruition, you have to make sure all 100 switches are on. If a single switch turns off, the entire project comes to a grinding halt. And the switches are painfully hard to push on yet randomly snap off in an instant. A brutal Sisyphean setup that saps the passion of even the most ardent entrepreneurial leaders.

the afterlife

I might put a concept back on the shelf for awhile, but I don’t give up. Over the following decade I repeatedly espoused sustainability to a most receptive US DOE team and personally entered and won the US DOE’s Manufacturing Innovator Challenge for Sustainable Luminaires. Which went on to inspire many others in the lighting industry, such as the team that developed and launched the wildly popular brand Lightly:

Hey, it only took ten years!